LETTERS FROM YANGCHOW - LETTER II By Stephen W Green from Shanghai, Yangchow and Chinkiang 1937

Smitten By Faith Issue # 00049 15th October 2022

In last week’s issue, you read the remarkable story of how, 85 years since the Letters From Yangchow ( 3 letters in total ) were written in 1937 by an American Missionary, Stephen W Green ( ‘W’) , they came into the hands of his son, Stephen H Green and then, how the letters were passed to me in Tokyo in 1984.

Last week, you read W’s first Letter I about the missionary family being stranded in Tsingtao ( now spelled ‘Qingdao’ ) during the escalation of the Second Sino-Japanese War. This second letter from W captures very vividly how he and his family tried to return home to Yangchow from Tsingtao during those early days of the war. Tsingtao was in the northern coast of China near Beijing. It was a long way from Yangchow. With minimal rail and road services, W and his family sailed from Tsingtao to Shanghai and then once there find a river steamer that would take them from Shanghai along the Yangtse River to Yangchow. It was very dangerous travelling in China then. They lived through Japanese air raids, attacks, food and other deprivations. Japanese soldiers were everywhere. Chinese cities were being attacked. Chinese soldiers and refugees were now ubiquitous. What were the missionaries to do? In the case of W, as headmaster of the Mahan School in Yangchow, his school was still open – but only barely ! So W’s only thought was to get back to Yangchow even though it was getting apparent that it was time for all foreigners to leave China.

By the time the Second World War started, China had already suffered much of Japanese aggression with the earlier First and Second Sino-Japanese wars. By 1937 Japanese troops were already skirmishing with Chinese troops in most of the major cities in China including Tsingtao, Yangchow and Shanghai. By 1943, at the height of the Second World War, most of these cities were occupied by the Japanese and most of the foreigners had fled - including, finally, the brave W and his family.

But I run ahead. In Letter II written in 1937 ( see below), W and his family were still in China, still hoping to continue with their lives and making the best of a worsening situation in terms of their personal safety. Join me now as we continue with W’s second letter – LETTER II. Note that I have taken the liberty to shorten and edit the original Letter II due to space constraints. I have also left some spelling ‘mistakes’ and typos as W had written in order to capture the immediacy and drama of the moment as W sometimes typed in darkness. Of course, once all 3 letters have been ‘published’ in Smitten By Faith, I will provide a bitly link for the paid subscribers to download all the 3 original letters. ]

LETTER II – BY STEPHEN W GREEN

December 12th to 22nd, 1937 – written from Shanghai, Yangchow [Yangzhou] and Chinkiang [ Zhenjiang ]

December 12th - Shanghai

Left : Shanghai in the 1930’s - bustling with style and wealthy with trade

Right : Shanghai just before the war. You can see the famous iconic bund and the Yangtse River.

Centre : modern Shanghai today with its incredible skyscrapers and skyline.

…. By the 23rd of August when we were due to have left Tsingtao [ Editor’s note : ‘Tsingtao’ is now spelled ‘Qingdao’ but I will keep to W’s original spelling ] , hostilities had broken out in Shanghai…..but it was not until the second week in October that women and children started going back to Shanghai. We, Ellen, the children and I, moved from a Russian pension to a cottage about the last [ week ] of September.

….I tried in many ways to get to Yangchow for the school had opened and my Chinese colleagues were begging me to return.

….[With] the Chinese Government officials refusing us a pass on the railway and requiring that I go via steamer [ from Tsingtao ] to Shanghai and from there to Yangchow rather than by rail, I could not get off until October 20th, at which time Ellen and the children came along with me as far as Shanghai.

Arrived in Shanghai.

…. We went to St. John’s and kept house there…

[ Editor’s Note : St. John’s refers to the famous Christian university St. John’s University ( SJU) founded in Shanghai in 1879 by American missionaries. SJU was regarded as the most prestigious private university in China. It was closed in 1952 by the Communist government.]

…While we were at St. John’s, Japanese planes flew over us daily, bombing Chinese positions sometimes far and sometimes as near as three hundred yards. Our house shook from time to time. Occasionally pieces of shrapnel fell in the compound which Stephen took delight in collecting.

December 12, 16, and so on until finished

Neither of the children were at all afraid. Benny [ their younger son ] used to forget to come in when planes started power diving from above our compound.…..

…..We had to avoid establishing fear complexes in the children, so we had standing orders that they could stay outside when planes were flying high but were to come in when they began to fly low and especially when they began to power-dive, but Benny and his friends too often had to be brought in by Ellen or by me or by his friends’ parents. I don’t remember whether or not I told you about little Benny’s remark to Ellen one day when they were walking across the grass and the ground shook with a bomb which had dropped near. He was quoting his little Chinese friends. He looked up into her face and said : “Mother, we’ll never surrender! We’ll never surrender!”

December 12th to 17th

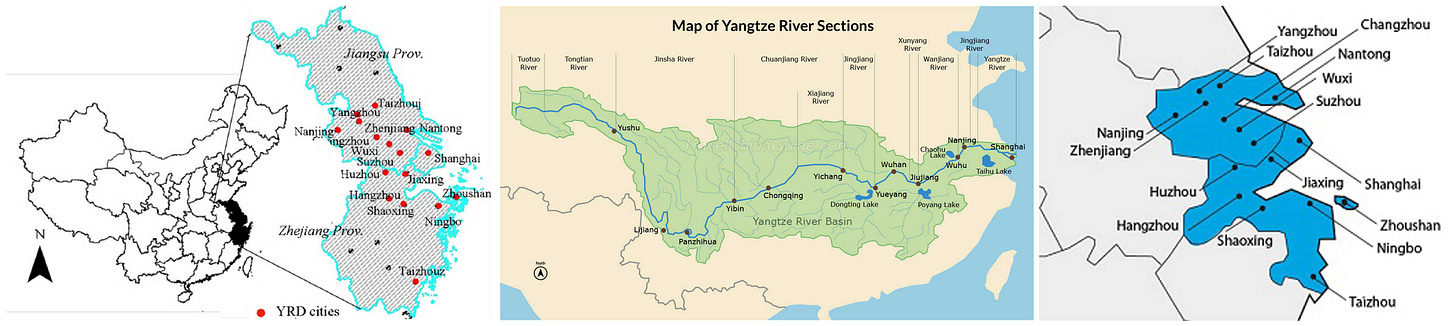

Middle : See the entire breath of the Yangtse River which stretches right across China.

Left and Right : Enlarged section of Jiangsu Province and the Yangste River Delta. Here, you can see all the towns travelled by W and mentioned in Letter II.

THE YANGTZE RIVER

[ Editor’s Note : The mighty Yangtse River is the world’s 3rd longest river running for 6,300 kilometres from the Tibetan Plateau to the river delta around the port city of Shanghai, cutting across China from west to east. The distance by boat between the port of Shanghai to the port of Yangchow, all in the same province of Jiangsu within the Yangste River Delta is only 194 nautical miles - not very far; a distance easily covered in a few hours by road or rail. But during the time of war, with only river steamer travel accessible, you can see here from W’s letter that even this small distance on the Yangtse River was a very arduous and dangerous journey. W does not stay in his letter how long they took. ]

On November 2, I started from Shanghai for Yangchow.

….No trains, of course, from Shanghai for a long time.

….Private cars and bus lines had been running the gauntlet up to a few days before at exorbitant prices and no baggage allowance and some were still going, but the danger was too great. However, British steamers had just started taking passengers over to Nantungchow [Editor : now spelled Nantongzhu] , a city on the north bank of the Yangtse River about six hours run from Shanghai.

Since its founding in Liverpool in 1816, the Swire group is a huge trading conglomerate in China, Hong Kong, Japan, Australia and the world. Butterfield & Swire, a steamship company was established in 1866 by John Swire in partnership with Richard Shackleton Butterfield.

Left and centre : the Butterfield Steamer in the 1930’s in Shanghai.

Right : Headquarters of Butterfield Swire in Shanghai in the 1930’s.

….We got on the first of the Butterfield Swires Steamers to take foreign passengers across. There were such crowds of Chinese trying to get on board that I had to shove a way through to police and customs officers to get the servants on board. I even had to climb up the side of the steamer, the hatchways were so crowded, though by and by they had gotten a gangway up to the first class quarters. Going down the Whangpoo, the river which comes up to Shanghai from the Yangtse – all steamers from the interior, China coast, or across the Pacific, have to come up this river to Shanghai – we passed many Japanese gunboats and many planes flew over, but only one burst of machine guns and no artillery fire right on the river. Of course, we could hear the guns and the bombs on the other side of Shanghai where the worst fighting was going on.

….We reached Nantungchow [ Editor : now spelled ‘Nantongzhou’]. We stayed overnight on the steamer and the next morning got into a lighter and started ashore.

….We saw at Tsengchiakou, the port of Nantungchow, a sunken Chinese Customs cruiser and the shell-ridden and partly burnt wharf of the Da Dah Steamship Co. There were a few Chinese soldiers visible from the lighter as we were going ashore, and standing off out in the river - which is here so wide that even on a clear day the opposite side can hardly be seen - were some Japanese gun boats, which juxtaposition did not make us feel too comfortable. But when we got ashore, people were all going about their business almost as if there was no undeclared war on. In fact, the Chinese on our lighter were most calm and cheerful. One coolie offered a poor old countryman refugee a cigar. The old fellow had never seen a cigar before. It was amusing to see him try to light it and to see the others poking a hole in it to make a draft and to hear the comments on his first cigar smoke.

…..It had rained the previous day so that the roads which are only unpaved, dirt roads were nothing but sloughs of mud from Tungchow [ Editor : now spelled Tongzhou ] to Yangchow. I went off to look for launches. ….There was still launch service, to Taichow [ Editor : now spelled ‘Taizhou’] , and from there another line to Yangchow, but launches were terribly crowded with refugees fleeing up-country, and their sailing times were uncertain. The head of the boatmen’s guild turned out to be a gentlemen, a Dr. Ching, who was very polite to us and let us have one of his own gasoline launches. There was just room in the forward cabin for our crowd … to sit packed rather closely.

….Before starting, Dr. Ching set us all up to a Chinese dinner. We bought ten live chickens, any number of eggs, tinned and powered milk, fruit, fresh and tinned, charcoal, cigarettes, and a peck of peanuts. My “boy” had brought some bread, jam, and other food stuffs. Mrs. Ancell’s cook did the cooking for us over a charcoal burner on the open after-deck. We ate our meals in courses because only one pot at a time could be put on the charcoal burner, so that sometimes a meal lasted about two hours.

We started off at four in the afternoon, flying an Asiatic Petroleum Co. flag (they are the company who sell Shell gasoline) as it was the only flag we could borrow, the APC having only one British flag and the Standard Oil only one American flag for their property in Tungchow, and the Christian Mission Hospital – the one which was bombed so badly – having only the one American flag which a nurse had made out of her nurse’s blue cape with red lining and a linen sheet. Of course no flag would have saved us from bombings if planes had flown over us, but we wanted some protection against having our launch commandeered by Chinese soldiers on its return trip when we would not be on it.

…. We travelled all night on the launch. Most of the men ….tried to sleep sitting on the hard wooden benches in the front cabin…. and the roof of the launch. It was rather hard, and a little chilly, and there were interruptions as we passed thru towns or came to narrow places in the canal, for I wanted to see everything that was going on, and then finally it began to rain.

….About eight in the morning we reached Taichow ( Taizhou ). The crew stopped there for breakfast and a rest, and then we went on. At Hsienniumiao, a village about six or eight miles from Yangchow by land, but about eighteen miles by water, there is a new drawbridge used by travellers which go from Yangchow up the Grand Canal to Paoying and Tsingkiangpu. ….The boatmen were unfamiliar from here on with the way, so I acted as pilot because I had been up and down ten of fifteen times on various pheasant shooting trips and in our little launch, but there were one or two places where we had to take a chance on shoals as the water level was high and the lake covered certain parts which at low water are banks of the channel. Any way, we got thru all right and arrived in Yangchow at four in the afternoon, just about twenty-four hours after leaving Nantungchow [ Editor ; now spelled Nantongzhu’ ] , which was really very good time.

YANGCHOW - at last

Above : Part of the Grand Canal meandering through beautiful old Yangchow

….My - how good a bath felt that night! Fortunately, I took it before supper, for after supper I found a problem on my hands which kept me away from the bed that I was so longing to get into. It seems that I was fated never to make up while in Yangchow, for the sleep I lost on the trip up.

Above : Mahan school - photo taken by W in 1930

….Mahan took in girls this fall. Oh, yes! We were very progressive, but it was meant to be a temporary arrangement only. At least, I promised that it would be temporary as soon as I heard that it had been done, for it would not have been fair to have made Mahan permanently coeducational. The principal, much against her will, had had to go away from Yangchow just at the time for opening school.

….I found that against my advice and school orders, boarders had been taken in to Mahan. I could not put them out at the late date that I got there, but I made their presence as boarders even less official than it had been before I got there. Of course, in the past our aim has been to eliminate day-students and to have all boarders, but in these days it seemed wisest to most of us to have only day students. There was the difficulty of possible night air raids – several times the gongs sounded the warning signals at night, but fortunately Yangchow did not have any actual night air raids. If the students stayed in the dormitories, there was the danger of a larger group being killed in a raid. If they went out into the W shaped trenches, at night there was the danger of their catching cold, not to speak of the loss of sleep. More constant supervision was necessary during this time than in ordinary times when a boarding department is hard enough to run. Though we required that all students who lived in the school have a relative or friend who would take all responsibility for them in case of trouble and who lived in Yangchow, I found that many boys did not have such a local guardian, and when we had to close and send the boys home, I found a few, even, whose guardians had themselves beat it without troubling to notify the school, so that some of the boys had trouble in finding someone to help them get home after we closed.

….The one day that we did have a real air raid I was in the school. ….I insisted that signals be obeyed and classes be dismissed when the “Urgent” warning was given and that the students scatter under trees and along the edge of the compound wall, or else into the trenches. The latter were deep enough and there were enough of them, but they had been made too narrow and I was afraid they might cave in and bury the children if a bomb fell too near. Of course none of the trenches or dug-outs anywhere were really proof against a direct hit (except that of the Russian Ambassador in Nanking [ Editor : now spelled ‘Nanjing’ ] who, I was told, spent thousands of dollars on his dug-out. But I did not want to have our children have that happen to them which happened to ninety boys and girls from a primary school in another city who all died either from wounds or from being smothered when their dug-out caved in. I had not minded the bombs falling so near in Shanghai, or the pieces of shrapnel cutting branches from trees over my head as the shells burst over St. John’s, and I did not even have any special qualms about myself in Yangchow, but there was a catch in my throat as I stood by the side of the trenches.

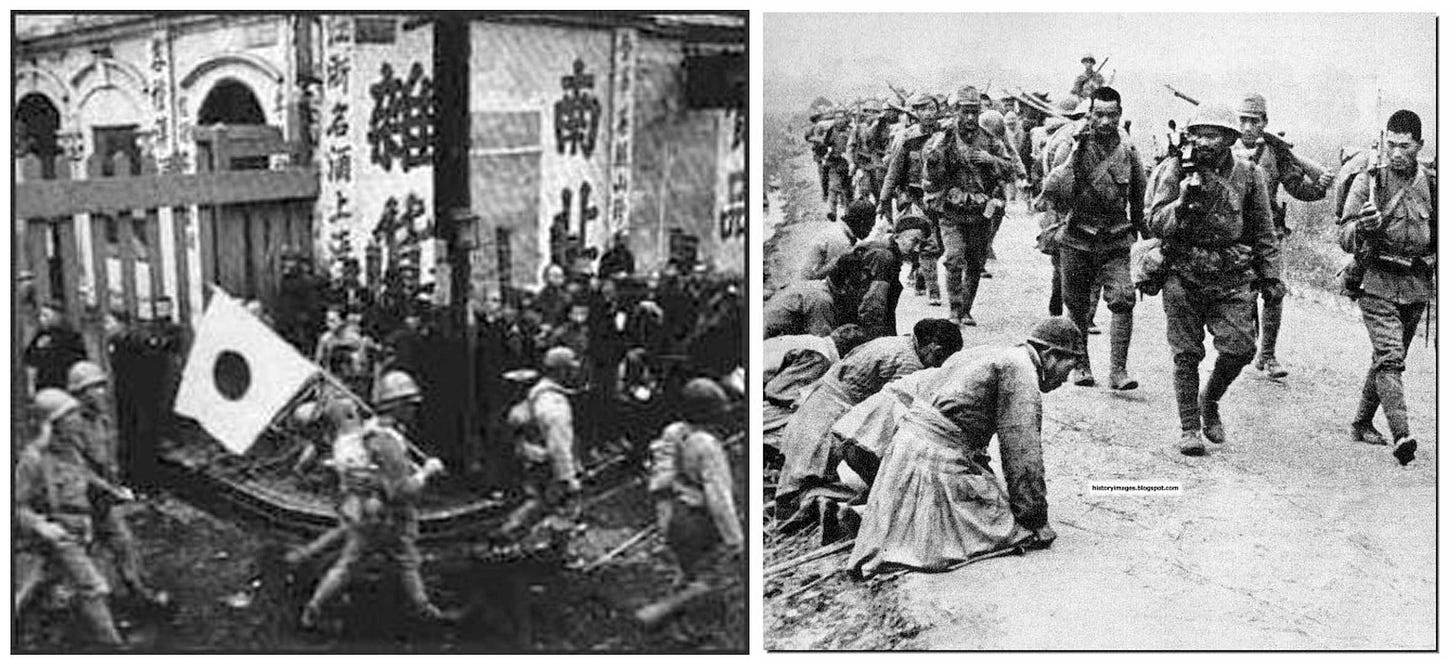

Above : Japanese occupiers in China during the war

December 22nd

…..Well, the bursting of shells over my head as I was at St. John’s [ in Shanghai ] had left me calm and unexcited – hardly more than interested, but [now] to see the planes fly over us in Yangchow as I stood by the side of the trenches and looked down into them at the little girls and some of the younger boys crouching in them, made a catch come into my throat. How glad I was when the government schools began closing and our own students and teachers began to be anxious to go home. We closed up on November 16 or 17. Even then, some of the teachers and students had difficulty in reaching home because launches had almost stopped running and canal boats of all sizes were being commandeered for transporting wounded soldiers away from Yangchow for fear of an attack which was expected as there was a rumour that the Japanese had landed at Tungchow [ Tongzhu ] and were advancing towards Yangchow from Jukao and the certain news that they had advanced to Wusih on the Shanghai-Nanking Railway.

….I was undecided whether to try to make Shanghai or to stay in Yangchow and see things thru. The strongest personal pull was Ellen and the children, of course, especially since Ellen was due for an operation sometime in the near future.…..Then on Saturday a telegram came ordering Fairfield and me to come to Shanghai. That decided me to make a try to get to Shanghai.

…..I made arrangements therefore to charter a vehicle for our party. All this and the paying off of servants and workers so that they would have enough money to last them at least thru December and part of January took time. Then we were not sure this would do after all, and I got busy and provisionally chartered a sampan, lending them an American flag so that they would not be commandeered. ….I had one small suitcase that I was determined to hang on to as long as possible. Then I put school account books in another suitcase, and in a larger one I had the servants throw a bunch of stuff that was hanging around in sight.

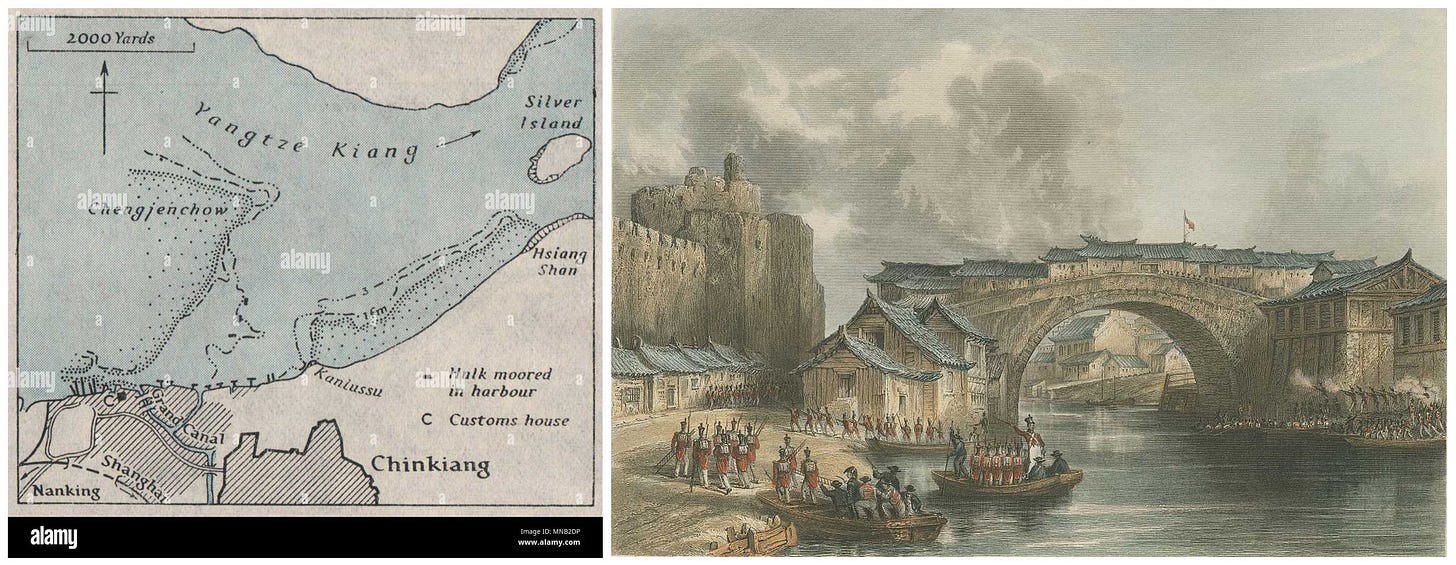

CHINKIANG [ ZHENJIANG]

[ Editor’s Note : During the war, to get to the then ostensible safety of Shanghai, it was not a simple straight line travel by road or rail. But, the Yangtse River was still open and the best option was first to get by road from Yangchow to the big port city of Chinkiang and from there find a steamer for Shanghai. ]

Left : Map showing the location of Chinkiang

Right : An old beautiful print of Chinkiang during the time of the Opium Wars with conflicts between China and the western powers in the early 19th century. See the bridge over the Yangtse River.

….To bargain for a special bus for our party, I got one for thirty dollars. Then I arranged for our people to come down. One Chinese lady teacher wished to go with us as far as Chinkiang. We took three servants with us as long as we had plenty of room, and then there were we foreigners – Leslie Fairfield, and Mr. Stirner, and I. …..Ordinarily the trip to Chinkiang would have cost, even for such a large party, but seven or eight dollars including baggage – eighty cents a person and twenty cents apiece for baggage, but before we got thru with rickshaws, busses and special tips and arrived at the C. I. M. hostel in Chinkiang, we had spent more than twelve dollars each (True, we foreigners assumed most of the share of Miss Chang, the Chinese teacher, tho she paid three times as much as she ordinarily would have had to pay).

At the C. I. M. hostel, they were very kind to us. Fortunately, we had brought enough bedding among us, for they had no extra bedding. We also gave others staying at the hostel a treat of some tinned butter and some tomatoes we had brought along. The butter lasted for two meals, then we ate peanut butter. One makes one’s own peanut butter in our part of China, for peanuts are plentiful. After three days, supplies began to run low, however, and prices of from the compradors were prohibitive for us; besides which, many kinds of food could not be bought for love or money.

…..Finally the commander of the British gunboat offered to Leslie, Workman, Stirner, and me (the non-British men who were in Chinkiang) the chance of joining a diplomatic party composed of the new Shanghai Consul-General for Germany, the Swiss Charge d’Affaires, the Dutch military attache, the head of the Hankow Red Cross-American, a Butterfield and Swires Steamship Company agent – English – on a dash for Shanghai via Kouan and then along the route by which I had come from Tungchow to Yangchow, and then via British steamer from Tungchow to Shanghai. A steamship company offered us a tug boat to Kouan, but said we’d have to shift for ourselves from there on. It was too risky for ladies to try to go that way, for we had heard that there was fighting on the north bank of the Yangtse near the boom and possibly also at Tungchow. We thought we might have to turn back from almost any point en route, and might perhaps have to strike off overland back into the country somewhere and possibly spend weeks in some village. The plan for the ladies to go on to the tanker seemed at the time so good that we decided to let them do that and that we four would join the diplomatic party and try to get thru, especially as we wanted someone on the Shanghai side of the fighting line in case Nanking were to be cut off from Shanghai so that one of us could go back to help our people if the Japanese took Chinkiang. Forster would be on the other side if the Chinese kept Chinkiang, for he was in Nanking at the time. That would leave some one on each side of Yangchow, both east and west, ready for eventualities.

….I won’t go into the details of that trip except to say that we got the same launch at Kouan by which I had gone up to Yangchow some weeks before. It had been commandeered by a Chinese major, but he let the boatmen take us along. We were not so well prepared for food, but made out all right. The diplomats had wired from Nanking and had first chance at any transportation available, but luckily for us there was room enough for the four in our party, and even room for all our baggage, so that I did not have to throw away any of my four pieces. Altho we ran out of gas when nearly at Tungchow, thru my friendship with the boat owners, we managed to scrape up five gallons from somewhere and get in all right.

We had to stay thirty-six hours aboard the British steamer at Tungchow.

[ SHANGHAI ]

Soon after I got here, I found that St. Luke’s Hospital needed office help, so I volunteered. Ever since I have been giving full time to the hospital as office secretary. I’m picking up in my shorthand, and, tho this letter does not show it, in my typing too. I’m writing this letter in the evenings and at odd moments. From the dates at the top of the pages, you can see that I began it on December 12 and that it is now December 22. I’m usually pretty tired, and one night while I was writing, the light bulb burnt out and I finished the page in the dark. I’ve been too lazy to read thru previous pages when I began at any time, with the result that there is probably much repetition. I’m making carbons and am asking your forgiveness for sending you these, as I just don’t feel that I can write eight or ten different letters of this length.

….Ellen was not feeling too good when I got back here the first part of December. But she has now gotten the proper kind of thyroid extract (which she will have to take practically all her life) and is pepped up so much that Dr. Pott says he is going to operate on her right after Christmas – gall bladder. In the meanwhile she is working every afternoon in the O. P. D. (Out patients Department) at St. Luke’s No. 2. ….We take in all kinds of patients there.

…. What about future plans? We do not have any, except for me to go back to Yangchow as soon as I can get passes from the Japanese military – Japanese consular passes are no use – and give our people there what help I can, especially by taking them money on which to live. Not much chance of school opening up for months to come. Our furlough is due in the summer. Perhaps we’ll come home then, perhaps before.

Our love to all.

[ LETTER III WILL BE PUBLISHED IN TWO WEEKS TIME ( on October 29th ). STAY TUNED . ]

______________________________________________________________________

Editor’s Note :

Dear Reader, thank you for reading this edition of SMITTEN BY FAITH.

ALL articles in every issue are FREE.

For those of you who upgraded to be a PAID Subscribers for US$ 60.00 a year, thank you so much ! All proceeds go to the Regina Apostolorum Foundation to promote Catholic higher education.

PAID Subscribers will also receive via Bitly link ( see the posts pinned above available only to paid subscribers ) the digital copy of the recent book by Joan Foo Mahony, ‘LATE HAVE I LOVED THEE’ and THE COLLECTED ARTICLES, VOLUME ONE 2021 and the recent VOLUME TWO 2022 of Smitten By Faith, a DIGITAL COMPILATION of all the previous year’s 2021 and six months of this year’s 2022 articles.

Paid Subscribers will also soon receive the Bitly link to full contents of ALL the Letters From Yangchow : Letters I to III.

For paid subscribers, simply click on the relevant Bitly links to receive the publications.

Paid Subscribers will also receive additional exclusive material from time to time.