A WORLD AT WAR - THE EXISTENCE OF EVIL AND TRUSTING IN GOD

Smitten By Faith Issue # : 000093 12 October 2024

Our 21st century world is a world at war. No, not a Third World War as such but it might as well be. My eyes are filled with tears as I try to list out ( in no particular order ) some of the bloodiest wars and conflicts of our modern 20th and 21st centuries. Aside from the terrible First and Second World Wars, we had : the war in Congo and the Rwanda Genocide, Nigeria and the Boko Haram, Sudan and Darfur, the Yemeni Civil War, the Syrian civil war, Afghanistan, Iraq, Myanmar, Russia and Ukraine and right now, each day, happening in plain sight before the world, the horrific genocide in Gaza and the daily bombings in Lebanon.

More than 200 million people have already been killed; entire villages, towns and countryside have been destroyed and there have been unimaginable deaths, suffering and maiming – men, women and children. Relentless bombings have led to huge displacements of innocent people and the world is now facing the biggest refugee crisis in a generation - on a scale never seen since the second world war.

Our modern century - the bloodiest in history - has become a shameless century of evil.

War in the early centuries had meant great battles. Some epic battles even made it to folklore. But war is war. War kills people - not just soldiers. War is an evil which causes immense and untold suffering. It did not take long before many great artists began to denounce the violence and suffering of wars - through their artworks. Let’s take a look at some 20th century painters to see how they responded.

Pablo Picasso, ‘Guernica’; oil on canvas ( 1937); Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid.

Measuring 3.5 meters by 7.8 meters, and painted in stark grey, black and white colours, Guernica is a very large painting by the famous Spanish artist, Pablo Picasso, one of his best-known works; a moving, powerful and definitive anti-war painting. In this painting, Picasso portrays his deep distress with the Nazi bombing of the Basque Spanish village of Guernica. That terrible day, when more than 5,000 civilians in a village with no military or strategic value were senselessly killed by the Nazis in support of the dictator Franco. Picasso’s surrealistic composition includes a gored horse, a bull, screaming women, a dead baby, a dismembered soldier and several severed limbs and body parts scattered around. Picasso’s ability to show modern warfare at its most primal – using animals - to illustrate the suffering Guernica endured is a blunt indictment of the terrible evil that surrounds us.

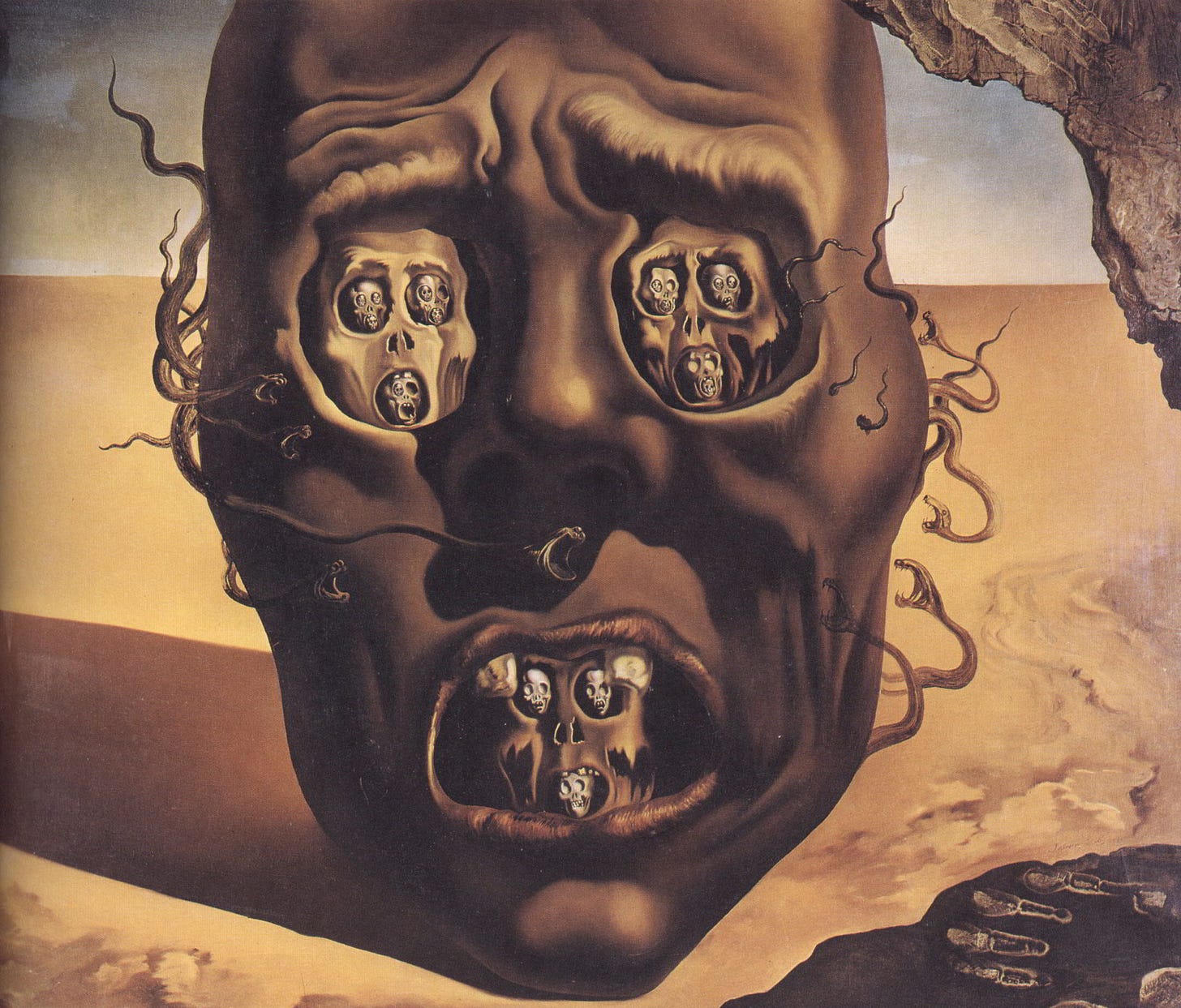

Salvador Dali, ‘The Face of War’ (1940); oil on canvas; Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Just as in the case of Picasso, the Spanish painter Salvador Dali was also hugely affected by the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and its atrocities when around one million people lost their lives during this senseless bloody conflict. Dali’s painting is hauntingly surreal. You see death staring at you with the human skull. The face of death is profound, sobering and so sad. You see this sorrow multiplied in the many more skulls that fill the eye sockets and open mouth. If you look at the bottom right hand corner of the painting, you will see a hand-print. Dali says that this is his own hand-print. He wanted to keep a part of himself within the painting – something he had never done before with his other artworks.

War has been part of humanity’s fabric ever since the beginning of time.

Indeed - let’s now go back to the 17th century when Europe was mired in the relentless and bloody ‘Thirty Years War’. As mentioned, already then, there were artists who were profoundly anti-war. The consequences of war were too terrible. Just take a look at the painting below by Peter Paul Rubens.

Peter Paul Rubens, ‘Consequences of War’ or ‘Horrors of War’; oil on canvas ( 1638-1639); Palazzo Pitti, Florence.

This very large painting by the renowned Baroque period Flemish artist, Peter Paul Rubens is a powerful allegorical anti-war painting. It is an allegorical representation of the Thirty Years’ War that all of Central Europe struggled through from 1618 to 1648. The consequences of this long war were dire – destruction of huge areas of Europe, the plague, famine and deaths. Rubens’ painting depicts Mars, the Roman God of War, marching from the Temple of Janus – with its open door which depicts war. Mars is presented with some choices. Continue marching on to war ? Or retreat and show mercy ? Venus, the Roman Goddess of love tries to hold Mars back. This is in vain. He chooses war. You see on the other side, Mars being pulled forward by the Alecto ( the ancient Greek Goddess of Anger ) with a torch in her hand. It is an energetic painting and you can see many figures. Aside from the cupids of Venus, the painting seems overwhelmed by the many monsters signifying the plague and famine that raged through all of Europe during this bloody war. Thrown to the ground is a woman with a broken lute as a symbol that harmony cannot exist beside the discord of war; and behind Mars, you see a mother anxiously grasping a child in her arms. Deeply religious, the Catholic Rubens cannot contain the pain, suffering and brutality of war.

I am no artist. What can I do to bring attention to the evils of war ? I want to get down on my knees to pray - for all this to go away. But I know too it’s not simply about praying. Prayer won’t take this evil away. So, why does evil exist ? Why does God let this happen ? How could a compassionate God allow this ? I search for answers. As a Catholic, I try to find the traditional explanations for this timeless question. And I am not sure if I can. So, here goes.

All Christians know about ‘The Book of Job’ in the Bible which tells the story of a man from Uz called ‘Job’ who is confronted with the most horrific trials of life and how he deals with this. Job represents not just suffering but innocent suffering. This man, Job – wealthy, upright, faithful and a moral man of the community - was suddenly given the mother of all sufferings when all that he had was taken away. Job had done nothing wrong and yet, God let Satan have his way with Job and we see the poor Job slowly but surely and relentlessly lose everything – his large family, his land, his wealth, his friends – everything! And yet, even though Job could not understand what was happening to him; even though he must have been totally confused ; even though he must have cursed his circumstances, yet – the Bible is clear - he never cursed God. He complained in his lament to God about the unfairness of his condition but he stayed true to God. What emerges from this is that we must trust God even when – and especially when - bad stuff happens to good people; and when we cannot understand God at all. This is called ‘faith’.

Finally, in the end, when Job had nothing left to lose, God restored all that Job had lost, and gave Job twice as much as he had before. God blessed him with a long life, seven more sons and three more beautiful daughters. And what does Job say ? He sees that God is all powerful and can do all things. He repents that he ever complained in his lament to God. He accepts that at the end, God’s purposes will be accomplished and that God’s purposes are good. So, for Job, he accepts that suffering is a part of life and God does not always choose to stop it. In The Book of Job, Chapter 42:5, Job says,

“ My ears had heard of you but now my eyes have seen you. Therefore, I despise myself and repent in dust and ashes.”

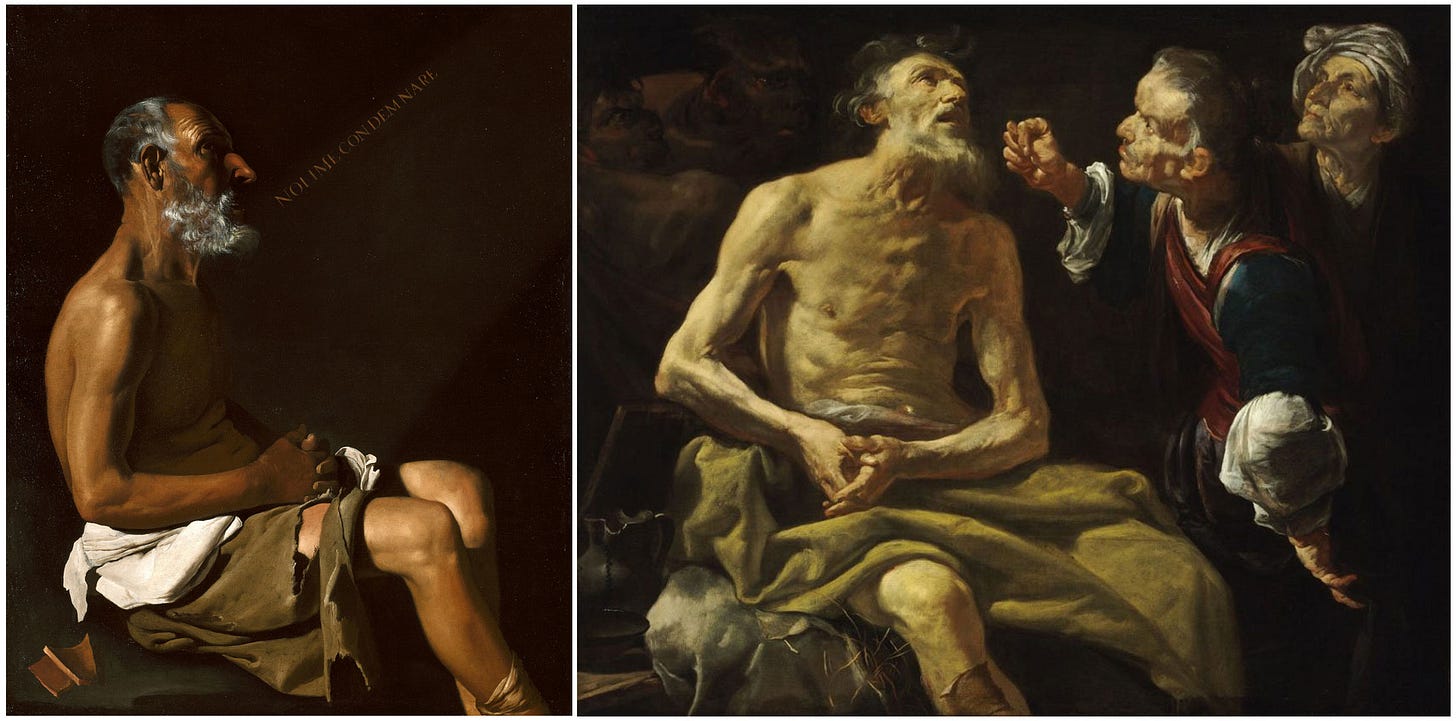

Right : Gioacchino Assereto ( 1600-1650), ‘Mocking of JOB’; oil on canvas; Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

Left : ‘JOB’ ; oil on canvas by unknown artist – from the Spanish School; Art Institute of Chicago

In the painting on the right above by the Italian artist, Gioacchino Assereto, an early Baroque painter from Genoa, you see the ‘Mocking of Job’. The artist shows a bereft Job tormented by his cruel fate but unshaken in his belief. He is half naked with only his loins covered in a rough, heavily creased blanket. Yet, he lifts his eyes towards heaven and prays for God’s mercy.

In the other poignant ‘Job’ painting on the left by an unknown artist from the Spanish School, you can also see a half-naked Job. But look again – there are some words in Latin coming out of Job’s mouth. Job is saying, —'Noli me condemnare’ which means ‘do not condemn me’. Job’s piety withstands the series of misfortunes which befalls him. He is resigned and more importantly, he still trusts in God.

The story of Job is about TRUST. Trust God for what we cannot understand or control. It is not easy to accept and live with a God whom we cannot fully understand. The story of Job is really not a definitive answer to the question of why God allows evil to exist. Doubts and questions are part of being faithful to God. None of us could ever claim to know God; we don’t know what God knows. How could we, mere mortals, know the answer to the question of why God allows evil to exist. But, in my case, I do know what my faith tells me - that God must have a good reason ?

There is a terrible statistic which shows that there has not been a single day since 1900 when there has been no war or conflict at any corner of the world. Will we ever have genuine peace one day ? We can only hope that this day is not too far away – since we know with well-founded dread that the evil face of humanity, with knowledge now of the most lethal form of warfare - nuclear bombs - may put an end to not just wars ?

_____________________________________________________________________

Editor’s Note :

Dear Reader

Thank you for reading this edition of SMITTEN BY FAITH.

We publish at least once a month. ALL articles in every issue are FREE so you can simply click and subscribe as a FREE Subscriber to continuously receive the articles automatically by email.